This trip is a

kind of modern archeology: going beneath the surface of the present, shaped by

the Soviet era and the Holocaust, to find traces of Jewish life. Instead of

studying how our culture was destroyed, let’s see what remains and reconstruct

imaginatively what was here before. Instead of relying mainly on historical

sources, different things become visible if we see things in relationship to

Yiddish (and hasidic) literature.

All images are linked to a larger version, just click on them. The larger image pops up in a new window. Most locations are given twice, first with their transliterated spelling from the Yiddish pronunciation and then the regular spelling.

It’s an

archeological expedition, uncovering traces of Jewish life from the midst of

the newly prosperous Poland. (How much richer Poland is than Ukraine! Here

there is lots of food to be found in stores in every town. In Ukraine in 2005

there was often very little on the shelves, outside of big cities.) All of the

Jewish traces are like scars in the body of Poland.

What’s the

point? Maybe this is all a “futile passion” (Sartre). Or you could say it is

necessary as the only real way to memorialize the past Jewish life in Poland.

|

|

| Konin 1 |

|

|

| Konin 2 |

|

July 10th,

2006. A visit to KONIN was inspired by Theo Richmand's excellent book about his

quest to rediscover and reconstruct his family town from before World War II. We

can locate the sites marked on Richmond's map: Beys Medresh (House of

Study), synagogue (from 1832), mikve, Jewish Gymnasium, and the rabbi's

house.

The synagogue is a Biblioteka [Konin 1,2].

The area around Konin was part of Czarist Russia, in contrast to

Poznan, which was Prussian, or Krakow-Lemberg (which was Austro-Hungarian

Galicia). Hence the Konin Jews were less influenced by German culture and

modernizing trends. Poznan, more likely, had Reform/liberal/maskilic Jews. My

friend Andrzey says the cultural differences are still visible, as in different

agricultural practices.

When we were standing near the Konin City Hall and I was taking

photos of buildings that were formally Jewish—the Jewish library on ul.

Zielova—a man rode by on a bike and said in Polish, something like "Do you

want to take it back?" or "You should take it back." He was about

60-65, and he seemed to know that we were looking for Jewish sites.

Later I ask

for a more exact translation from Andrzey. Maybe "If you want to take it

back, put it on the bike and get lost." (Another interpretation: it was a

generous offer, "Take it on my bike and go!")

"If I translate that," Andrzey said, in jest, "I would be betraying my people." Andrzej explained that there is currently a discussion in Poland about reparations of Jewish property. It is amazing to realize that 60% of Konin was Jewish. Some Poles are uneasy about Jewish tours, fearing claims on ownership. Others are philosemitic and want to learn more.

This trip allows us to understand better the cultural lines that

separated Jews of Prussia, Russia, and Austro-Hungary. Polish and Yiddish were

spoken in these areas—but in contact with German vs. Russian and Ukrainian.

July 11th: By train from

Poznan to Warsaw and then Lublin. Stop in the nearby shtetl Łeczna with a synagogue dating back to

1648 [Łeczna 3,4,5,8].

July 17th. WARSAW: Peretz Street formerly Tsegliana (Ceglana,

Brick) St. [Warsaw 22-27].

|

|

| Warsaw 22 |

|

|

| Warsaw 23 |

|

|

| Warsaw 24 |

|

|

| Warsaw 25 |

|

|

| Warsaw 26 |

|

|

| Warsaw 27 |

|

In fact, the Jewish remaining buildings from before the war were made of brick, then covered in some kind of plaster or stucco facing; now we see the exposed brick on the unrenovated buildings. Interesting to note that there was a brewery at the northern end of Tsegliana St., and Peretz must have been able to smell the hops in the factory that was already operating in 1910.

Peretz lived at No. 1

Ceglana St. [Warsaw 14,15] Should try to get photos or paintings of this area

from the period Peretz lived there (~1890-1912). I may have had a relative in

the Jewish students' residence hall: Alex Frieden's older brother Yakov Ziv,

who studied in Warsaw around 1900. A contemporary of Peretz!

|

| Warsaw 14 |

|

|

| Warsaw 15 |

|

That part of town—now

in the center of Warsaw—was previously a working-class area that had factories

and warehouses. Many of the prewar buildings were built around a central

courtyard. To see a full street that survived the war somehow, look at Prozna

St. with the typical tenements and courtyards [Warsaw 14-15?]. All of the bare

brick is visible. Though possibly most of the buildings had plaster facings in

white, grey, yellow, melon. Built in 1880-90 with the usual inner courtyards.

|

| Warsaw 17 |

|

Nożyk Synagogue [Warsaw 17], the only one to

survive the war in Warsaw, built around 1900.

|

|

| Miedzeshin 6 |

|

|

| Miedzeshin 12 |

|

|

| Miedzeshin 18 |

|

MIEDZESHIN, summer vacationing area SE of

Warsaw where Peretz and his family went by streetcar. When you walk in, you

really feel that you’re entering a

forest [Miedzeshin 6,12,18].

|

|

| Miedzeshin 8 |

|

|

| Miedzeshin 10 |

|

|

| Miedzeshin 11 |

|

I shot photos of typical houses from a century ago

[Miedzeshin 8,10,11]. Is there a way to determine now where Peretz lived when

he was here?[14, 15].

|

| Miedzeshin 14 |

|

|

| Miedzeshin 15 |

|

This one seems later, influenced by Bauhaus [7].

|

| Miedzeshin 7 |

|

Also got

some images showing how the train service has been debased [Miedzeshin 1,2].

|

| Miedzeshin 1 |

|

|

| Miedzeshin 2 |

|

Does this look like it could have been a shul? [Miedzeshin 16]. One,

with a tower, reminded me of the house of the Rebbe of Kotsk [Miedzeshin 19].

|

| Miedzeshin 16 |

|

|

| Miedzeshin 19 |

|

July 14th. To GER (Gora Kalwar) to see the court of the

Ger Rebbe. Impressive courtyard, imposing red brick building [Ger 8,9,10] and other buildings [11,14].

|

|

| Ger 8 |

|

|

| Ger 9 |

|

|

| Ger 10 |

|

|

| Ger 11 |

|

|

| Ger 14 |

|

In LUBLIN, see the Cracow gate [Lublin 15,16], the Old (Jewish)

theater, the Yeshivat Hakhmei Lublin [Lublin 17,5], a prayer house [Lublin

1,12].

|

|

| Lublin 15 |

|

|

| Lublin 16 |

|

|

| Lublin 17 |

|

|

| Lublin 5 |

|

|

| Lublin 1 |

|

|

| Lublin 12 |

|

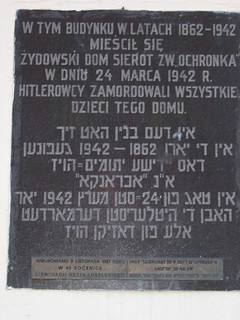

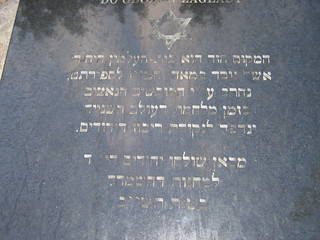

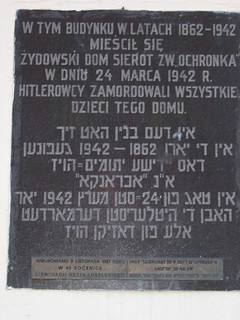

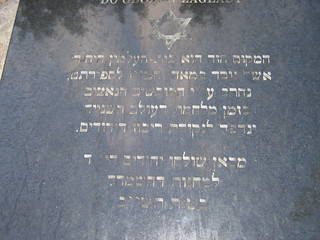

Plaque at the site of the Seer of Lublin’s house [Lublin 3], in Polish,

Yiddish, and Hebrew. Plaque at the site of the Jewish orphans’ house,

1862-1842 [Lublin 7].

|

| Lublin 3 |

|

|

| Lublin 7 |

|

Warming up for the part of my journey that is more pertinent to I.

L. Peretz and Yiddish literature. As we travel SE from Lublin, the landscape changes from

wheat-fields and other farms to forests and sandy terrain. Why is this soil sandy?

A distinctive geological process? Resulting in one of the poorest regions in

Poland.

July 18th. From

Lublin to Chelm, stopping to look at a couple of shtetlekh along the way.

Dorohucza was nothing special [1,2], but you never know. Stone mill [D Mill].

In Chelm, we saw the synagogue [3 photos] and the market.

The

synagogue is now a bar: McKenzee Saloon. There was a small Jewish museum on the

main street in town.

Then continued on to TISHEVITZ (Tyszowce)

which appears in Peretz's Bilder fun a provints rayze and in

Singer's story "Mayse Tishevitz" (translated in English as "The Last Demon.") To me this looks like a typical

Jewish house or inn [Tishevitz 1]. The entrance to the town [Tishevitz 3].

|

|

| Tishevitz 1 |

|

|

| Tishevitz 3 |

|

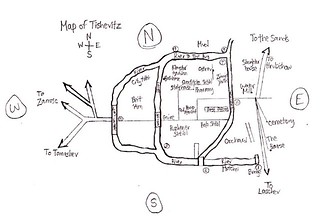

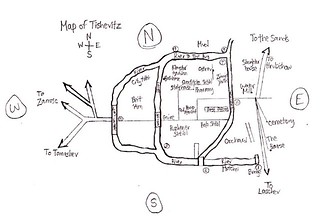

Brought with me a sketch of the shtetl from

the Tishevitz Yizkor-bukh. [Tishevitz map]

|

|

| Tishevitz Map |

|

|

| Tishevitz Map--English Translation |

|

There have been many changes

since 1933, including filling in some of the river tributaries. But we seemed

to be able to make out some of the hasidic shtiblekh [Tishevitz 4?] and the

Gemine community building [Tishevitz 2?].

|

|

| Tishevitz 4 |

|

|

| Tishevitz 2 |

|

There were hasidim from the Trisker,

Ruzhener, and other rebbes. Maybe they had a connection to this older brick

house [Tishevitz 5], which has since been expanded.

According to a local man [Tishevitz 10] who

told us that his mother helped save Jews, the town was 50% Jewish, 25% Polish,

25% Ukrainian.

|

|

| Tishevitz 5 |

|

|

| Tishevitz 10 |

|

The Jews were the merchants running the shops. The Poles were in

administrative positions, and the Ukrainians worked the land. The father of the man we spoke with was

Ukrainian and was killed by Poles who were working with the Germans. He showed

us where the Nazis killed the Jews. There is a memorial plaque [Tishevitz 6] on

the east side of town, about 200 meters beyond the river and bridge. He said

that thousands of people were buried under the sands.

|

|

| Tishevitz 6 |

|

|

| Tishevitz 7 |

|

|

| Tishevitz 8 |

|

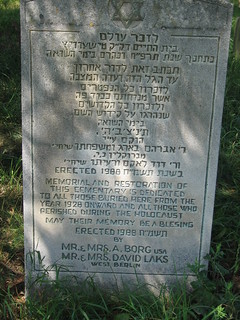

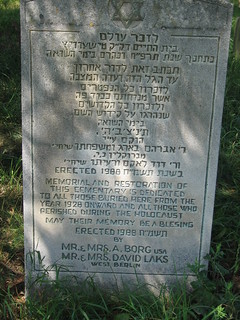

Saw the new cemetery [Tishevitz 7,8]; the old

Jewish cemetery was destroyed and a house was built on top of it. There is a

memorial stone [Tishevitz 11, 12].

|

|

| Tishevitz 11 |

|

|

| Tishevitz 12 |

|

Then on the road south to LASHCHEV (Łaszczów),

which was the second town Peretz visited, and a year later he included it in his

story “Ha-mekubalim” ("The Kabbalists"; Hebrew, 1891; Yiddish, 1894.) Wandered around a bit and noted the typical wooden houses

[Lashchev 1]. Eventually we came upon the synagogue on the south side of town.

Exciting moments, caught on videotape [Clip, including footage of Kobi Weitzner, a Yiddish writer who works with the Yiddish Theatre in Warsaw.]

A massive ruin [Lashchev 2,5]. It seems to be somewhat in the style of the Zamosc synagogue: square, with high,

vaulted ceilings [Lashchev 4]. The ruin is an apt representation of the decline

described in Peretz's story. But it is interesting that the ruin is so similar

to the shul in maskilic Zamosc - unlike the shtiblekh of the

different rebbes in Tishevitz.

Maybe Peretz was referring to another Yeshiva?

Or maybe he overstated the hasidic leanings of the teacher and pupil in his

story. In any case, I now have images to go with the Peretz story; a poor town

could no longer support the Yeshiva, leading to its demise. Or was this

synagogue destroyed during World War II? No one to ask.

Nearby, another building may have been used

previously as a synagogue [Lashchev 7]. I think I read that it was bought, not

built for Jewish use. I think I was told that it was used more recently as a

movie theater.

|

|

| Zamosc 16 |

|

|

| Zamosc 17 |

|

In ZAMOSC I am struck by the impressive stone

architecture, epitomized by the town square [Zamosc 16,17]. The Old Square is astonishingly beautiful,

unlike the one in Lashchev (in the Peretz account, Bilder fun a provints

rayze, there are goats grazing in the market square). Peretz was

understandably shocked when he was sent from the stone town to the poor wooden

town Shebreshin.

|

|

| Zamosc II, 24 |

|

|

| Zamosc II, 1 |

|

Zamosc gets its name from Jan Zamoyski

(1542-1605), memorialized by an equestrian statue in front of the palace

[Zamosc II, 24]. Renovations are making it more difficult to separate old and

new [Zamosc II,1].

|

| Zamosc II, 9 |

|

|

| Zamosc II, 15 |

|

|

| Zamosc II, 18 |

|

After some difficulty I checked into a room

in the relatively posh Zamojski Hotel near the Old Square and Peretz St.

[Zamosc II, 9,15], where he may have lived [Zamosc II,18]. Incidentally, any

old square reminds of Peretz’s play, Bay nakht afn altn mark (At Night

on the Old Square).

July 19th. Walked around early in

the morning, focusing on 3 streets associated with I. L. Peretz: Staszica,

Jerusalem, and the one now called Pereca St. Zamosc is a beautiful, small town.

In connection with this enlightened tendencies it is significant that City Hall

towers over Zamosc—not a church.

The ramparts are also impressive [Zamosc II,

13]. In his memoirs, Peretz recalls that during his childhood part of the wall

was dismantled.

|

|

| Zamosc II, 13 |

|

|

| Zamosc II, 11 |

|

It was home to Shlomo Ettinger, author of Serkele.

Italian architects made Zamosc into Poland's only coherent Renaissance

city, according to some guide books. One of the distinctive buildings is a row

of butcher stalls [Zamosc II, 11].

|

|

| Zamosc II, 20 |

|

|

| Zamosc 1 |

|

|

| Zamosc 5 |

|

ZAMOSC was a sophisticated town; one masterpiece is the Italian-style,

fortress-like synagogue [Zamosc II, 20]. Peretz says it was the “Paris” of

Poland. Amazing sixteenth-century synagogue [Zamosc 1,5].

|

|

| Zamosc 7 |

|

|

| Zamosc 8 |

|

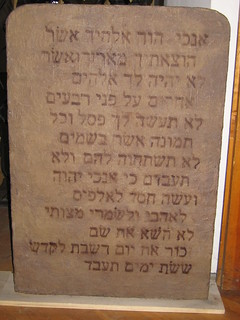

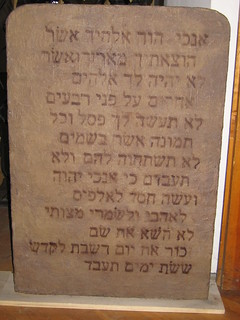

Inside, a tablet of

the first half of the 10 Commandments [Zamosc 7], and the second half [Zamosc

8].

|

|

| Zamosc 9 |

|

Spectacular interior [Zamosc 9].

|

|

| Zamosc 10 |

|

|

| Zamosc 11 |

|

The Aron Kodesh, to hold the Torah scrolls

[Zamosc 10,11].

|

|

| Zamosc 14 |

|

|

| Zamosc 4 |

|

Original ceiling painting of a shell design [Zamosc 14]. Side,

vaulted corridor [Zamosc 4]. Nearby buildings, around where Peretz lived

[Zamosc 15].

|

|

| Zamosc 15 |

|

From Zamosc I went back to SHEBRESHIN and

found the synagogue, which we missed the first time around. [Shebreshin 6,4] Took

pictures of it and of some wooden houses nearby [Shebreshin 7,9,10,11]—possibly

similar to one that Peretz lived in when he was sent into exile when he was

about 14, for bad behavior in his studies.

|

|

| Shebreshin 6 |

|

|

| Shebreshin 4 |

|

|

| Shebreshin 7 |

|

|

| Shebreshin 9 |

|

|

| Shebreshin 10 |

|

|

| Shebreshin 11 |

|

The synagogue is now a cultural center, and

they have many fine puppets on display. Bought a miniature oil painting of the

synagogue. [Shebreshin Shul]

|

|

| Sheb. Shul |

|

Then I pushed on to towns mentioned by I. B.

Singer: Gorai and Frampol. The first is really tiny, just 50-100 houses, and

must have been much smaller in the time Bashevis referred to, late Middle Ages.

A sign in the town square indicates that

Gorai was founded in the 14th century.

Unlike most of Poland I have seen, this area

is somewhat hilly. Then down the hills to much larger Frampol, where I found the

unmarked synagogue across from the churches. Apparently it is being used for

apartments. Also many houses that looked shtetldik, plausibly small

Jewish dwellings. Interesting place. Need to get the images from my video

footage.

|

|

| Janow-Lubelski 1 |

|

|

| Janow-Lubelski 2 |

|

7/19. I stopped while passing through Janow

because I thought I saw a synagogue façade on a building that had been turned

into a shop [Janow-Lubelski 1,2]. The salesperson denied it, but there were 4

central pillars inside, suggesting a bimah, in addition to the elaborate

entrance.

|

|

| Rzeszow 1 |

|

|

| Rzeszow 2 |

|

|

| Rzeszow 3 |

|

|

| Rzeszow 4 |

|

Then an hour drive south to Rzeszow, which

people called Moseszow because it was so heavily Jewish. I see the two 17th

century synagogues [Rzeszow 1,2,3,4] but don't know about the Jewish part

of town, houses shops. There is a stone marking the site of the Jewish cemetery

[Rzeszow 5].

|

|

| Rzeszow 5 |

|

July 20. West to TARNOW. Saw the impressive bimah [Tarnow

1,2,6] and other remnants.

|

|

| Tarnow 1 |

|

|

| Tarnow 2 |

|

|

| Tarnow 6 |

|

You never know what you may find—like this

restaurant ensconced in what must have been a synagogue [Tarnow 9,10].

|

| Tarnow 9 |

|

|

| Tarnow 10 |

|

Then had trouble finding the route out of town to Bobova, ending up

on narrow roads crossing a mountain. It took so long that I abandoned the

longer route. Enjoyed seeing the Carpathians, ate a river fish for lunch, and

headed north via Opotow and Radom to Kazimierz.

Too long drive to Bubowa through some forests and across a

mountain.

|

| Bubowa 1 |

|

|

| Bubowa 2 |

|

|

| Bubowa 3 |

|

|

| Bubowa 4 |

|

|

| Bubowa 6 |

|

Finally inside the Rebbe's shul [Bubowa 1,2], with restored bimah

[3,4,6] and some traces of original color paintings [5, BubowaWallPainting].

|

| Bubowa Wall Painting 5 |

|

Rebuilt in 2003, the Aron Kodesh area was restored well, I think in

only slightly garish greens, blues, reds, gold (sponsored by Asher Sharf of

Brooklyn.) Saw the Carpathian Mtns from the road Grybow – Gorlice.

|

| Kazimierz 2 |

|

|

| Kazimierz 8 |

|

Kazimierz-Dolny [K-D 2]. Amusing to see the preserved shtetl that

already served as a movie set for Yidl mitn fidl in 1939. It was dark by

the time I shot the town square [K 8].

As in Zamosc, the butchers’ stalls have been preserved [Kazimierz

6] Some of the old wooden houses have a lot of character [K 10].

|

| Kazimierz 6 |

|

|

| Kazimierz 10 |

|

But after seeing Zamosc, Shebreshin, and Lashchev, the rest is

anti-climactic. Thought to add: Tishevitz and Frampol and dozens of kretshmes

(inns).

July 21.Olei regel (Pilgrimage)

|

| Kotsk 7 |

|

To Kotsk, a small, quiet town, but very pleasant [Kotsk 7]. A few

well-preserved old Jewish houses, including the house associated with the

Kotsker Rebbe [Kotsk 2,3,5].

He isolated himself from the world for 20 years,

some people say, in that unused wooden tower [Kotsk 4].

|

| Kotsk 4 |

|

Poor village with a

stone church in the main square [Kotsk 8].

|

| Kotsk 8 |

|

Now I have a clearer image to associate with the Rebbes of Ger,

Bobow, and Kotsk, which could make it easier to read their works.

Need to make documentary films on the great Rebbes and their courts.

Also on the classic Yiddish authors.